INTERVIEW

Brian Joseph Davis

by Paulo Mendel

The last century was distinguished by new compositorial strategies and by tools that were not part of a musician’s sphere. It is increasingly common to see composers that do not work with musical notation and conventional instruments.

Significant changes regarding computer interaction are yet to come; however, those will not be limited to hardwares and softwares. From the relationship between the copy/paste command and sampling, to compiling organic sounds in order to generate an electronic musical structure. we are in a two-way route between the real and the virtual.

Brian Joseph Davis, who agreed to be interviewed by us and to talk about his creations.

BlankTape: Firstly. I wonder if you could talk about your experience with Original Soundtrack (“Trilha Sonora Original”, 2008), a performance in which you manipulate the looping audio menus of 20 DVDs to generate a musical composition with the duration of a feature film.

Brian Joseph Davis: I did that because I wanted to make something unquestionably beautiful, something like an early Gavin Bryars work. Warm and dense. It combined my critical love of technologies-for-listening, and my near religious love of loops and soundtrack music. In some performances, I used the volume controls on the TVs. Other times, I had to use a mixer to control the sound in large venues.

I think what I like most about “Original Soundtrack” is the slim window for this to have happened as a music work. Looping menus are being phased out. I noticed this on higher-end DVDs, like Criterion. Is a menu that seems overdetermined now considered declasse? An example of “utility music” (an old snobbish term)?

It’s also scored (with a graphic score) and that was something I had never done before.

It’s a simple idea but it nearly killed me physically and financially. I toured this to three cities and each production involved finding 20 television sets, 20 DVD players and, in each case, my funding was either reduced right before or. in one example. canceled the day before I left on a plane. Very boring subject, I know. but for art like this, it’s 90 percent of the work. So for now I am concentrating on writing and adapting works for performances. Working with words and performers is a very durable idea. I never want to see another cathode ray tube again! New flesh be damned.

BT: You are also a book author, and you have written performances like Voiceover (2009) and Johnny (2007) , both of which originated from extensive film dialogue research. As much as this work is founded on the notion film, you have utilized the concept of sampling, a musical resource, to shape the works. Which relationship do you establish between words and music. and why cinema? Does it serve as a compositional element that is anterior to the work (a standard characteristic in your creations)?

BJD: Last month, Matt Timmons at CalArts called me a post-cinema artist. I thought it was pretty apt: i.e. films without making films. Why cinema? I think because it’s a social art. It’s an art that implies an audience and. in that, a sociology. I’m continually drawn to a lingua franca and want as many people as possible to understand a work. Film grammar is very understood across cultures and languages.

BT: The overlapping of 60 layers that correspond to 60 people singing the same tune is one of the formats of Yesterduh (2006). You also present tracks featuring individuals in the process of creating the lyrics. given that your instructions included not rehearsing. The subjectivity of perception is essential to the construction of this work. One of the parameters that differentiate its production is the fact that it is not about an absolute registry in a specific data medium (like DVD or vinyl): it is about an individual registry in people’s memories. How was this process?

BJD: It was a very difficult process to negotiate. I tried to make it the least exploitive as possible – people were paid, I built a nice recording booth with ornate rugs on the floor – and most people had fun. Some struggled (one man gave me the money back out of shame), but most found it an interesting challenge and memory exercise. and were genuinely surprised and entertained by what their brains did to this particular song.

BT: In Greatest Hit (2006), you condense various hits performed by several artists in an unique track, in accordance with the themes – such as All You Get From Love is 22 Songs and I’m Every Song, raising the question: “In this busy. hectic world. who has time for an entire album?”. Unlike Yesterduh, produced in the same year. this overlaying seems to be more focused in finding points of convergence instead of exploring differences. Does “Greatest Hit” criticize the structures of pop music. or is its critical connotation restricted to contemporary speed? What is the role of pop culture in your poetic?

BJD: Very nice catch on the connection/differences between these works. With Greatest Hit, like Original Soundrack, it was a matter of timing. That time was really the end of the album-as-work and the rise of the mp3 playlist. A greatest hits collection harvests from multiple sources to give an audience exactly what it thinks it wants. My idea was to extend that process to tracks themselves. With layering the tracks. would those elements that fans like become sharp and foregrounded while others would be. literally, canceled out signals? The result was unlikable likability.

I don’t claim any critique of pop culture. I am part of pop culture – the sarcastic part. All culture is popular some of it a little less so. What I did in these works was just primitive hacking of technologies that were.

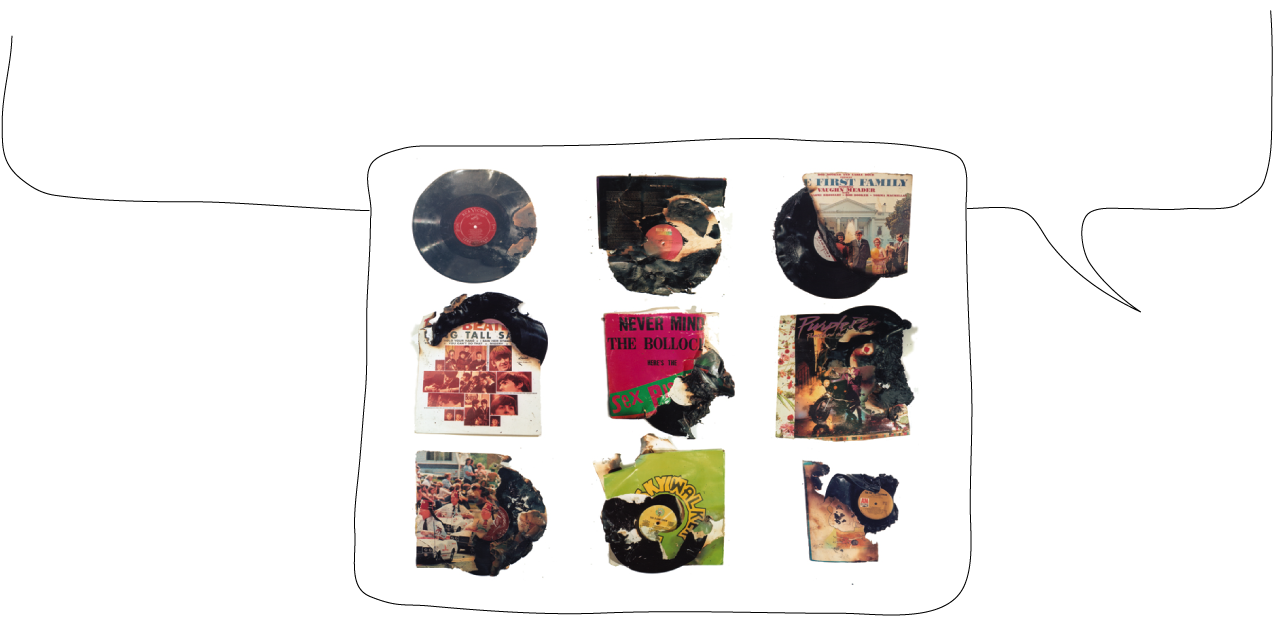

BT: In 10 Banned Albums Burned then Played (2005). you utilized. once again, vinyl records as raw material. In spite of the diversity of the artists selected for this work, which assemblies The Beatles, Prince, 2 Live Crew, Dead Kennedys, and even Stravinsky and Mahler, all the results sound like a Noise or Industrial remix. It seems like the handcrafted manipulation of this medium, the vinyl. is related to the effects reached by softwares and plugins in the production of rock and electronic music. How do you perceive the digitalization of music?

BJD: Funny, I was at a party last night and the digital poet Bill Kennedy was bringing up “structuralist pop music”. Bands that name themselves or their works after the technology they use: 808 State, the disc Superfuzz Bigmuff at Mudhoney. And so on. What I did with these artworks isn’t so different from what those bands did intuitively with their naming.

As for “10 Banned”, yes, that’s quite the collision between analog and digital. and within that collision is a joke a lot of people miss: that with digital tools. ideas of “banned” or censored information, come down to bandwidth and nothing else.

UA vinyl sample will always sound like a vinyl sample: hip hop, industrial dance. avant garde work. It’s the inherent flaw of vinyl! What’s interesting is that though it’s a digital marriage – vinyl to digital sample – it’s now a “dated” digital sound.