A game may be at first glance understood as a program, an application. Perhaps this initial confusion takes place more because they share the same platform than due to proper interface similarities. The essential difference between games and software lies in their purpose.

Software is used as a means to an end beyond itself. We open a word processor to write an essay, a contract or a guest list for a party. Games, however, only serve for playing. Their goal is in the act of playing itself. In this sense, games are related to art – especially those where winning is not that important. More than any reward for beating a game, whether that means saving the princess or the world, it is the pleasure of playing that makes a game such an immersive experience.

|

|

|

Video Ravingz (2002 | Cory Arcangel) is a hacked version of the game “Super Mario Bros 2”. where the player wins by simply inserting the cartridge. By tampering with the game programming Cory invokes a party mood with a chiptune soundtrack and an image that is manipulated to its total abstraction. The result reminds us of Synchromy (1971 | Norman McLaren), a pre-videogame animation where the image creates the soundtrack. The image in the cartridge is Super Mario Movie (2005 | Cory Arcangel), a 15-minute film programmed in the Nintendo game. |

In interpersonal relationships, games have always been a resource for integration and competition, frequently used in group dynamics sessions, in teaching students, in actors’ rehearsals, in therapies, as well as sports and leisure. It’s in the act of playing video games, especially against artificial intelligence, that the verb to play first starts to hold the meaning of a very specific interaction that we can develop with any machine.

“people use software,

but they play videogames.”

– Pippin Barr

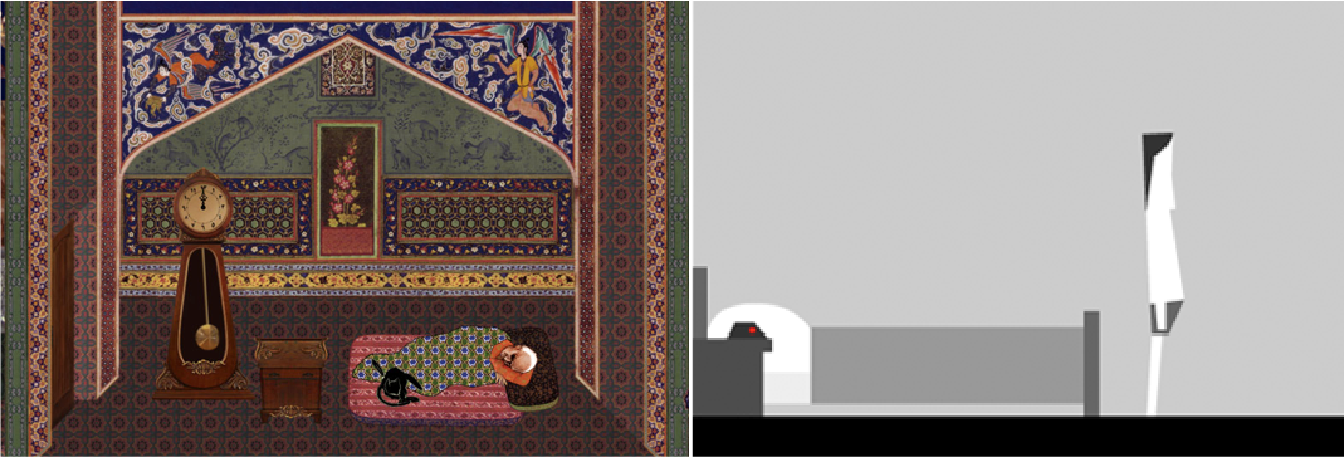

The Artist is present is a game based on the performance where Serbian artist Marina Abromovic remains seated while people in the audience, one by one. sit in front of her for an indefinite period of time. For that. long queues were formed at the MoMA in New York. The audience spent hours waiting to meet the artist. In the game, all the situation of entering and waiting at the art institution works as a kind of prologue to Abramovic’s work, possibly longer than the performance itself that takes place with the artist. The game runs in real time. therefore players are advised to be patient and to pay attention to the real opening times at the museum.

When we play, a series of choices are made, according to the rules of the game and the strategies we create. However, some games stand out in that they do not present their obstructions in the form of a tutorial. Players go through stages of contemplation, doubt, reflection and experimenting as they face a work that lies to be discovered. The rules are only unraveled as the interaction goes deeper.

This language-construction process establishes a sort of videogame heuristics. Good players become able to quickly recognize problems (puzzles, quests etc.) and which options they have available to solve them (on the interface. keyboard. joystick etc.). Even with some freedom of action, we know how to recognize mechanisms and effectively establish communication with the system.

That is perhaps why the human-computer relationship may be, in some specific interactive artworks, curiously more “natural” than if we were actually in front of the works themselves, not knowing how to behave and afraid the security guard is going to point out a sign that we hadn’t seen: “Please don’t touch”. Failing in a game is not embarrassing. Mistakes are often the only way to understand the rule, and after that, a solution.

|

|

Minecraft is an independent project by Swedish programmer Markus “Notch‘ Persson that has sold over 25 million units. Without any rules being proposed, players are faced with the goal of survival. In order to do that, they must explore and cultivate natural resources and transform them into food and functional objects. With similar properties to LEGO toys, in-game creations go beyond the game itself, as in the case of the images above, of a 3D printer or of inteligência artificial with biological qualities. Minecraft was also the starting point for a different game, Chain World by Jason Rohrer, a MOD that was devised to be passed from hand to hand in a pendrive that contains the game’s only copy.

|

Independently of the discussion concerning games as works of art, videogames are recognized as an important cultural phenomenon, both for the quality of the games and for the creative ways in which players/creators appropriate them. While keeping their pop product features, consoles are always ahead of other electronic appliances, even of the latest TV sets and computers.

There are already 3D-image consoles that fit in a pocket; the player’s body or voice controls the interface; several games can be opened in one’s favorite cell phone, browser or social network, anytime and anywhere. This means that, at least in the last 30 years, children and young people can access the most advanced technologies of their time, which, besides providing fun, have become inspiration or creative tools for musicians, painters, graffiti and comics artists, filmmakers, videomakers, poets, whether they are established artists or not.

“My name is Max.

I write software to help humans

communicate with computers.”

– Max Weisel

|

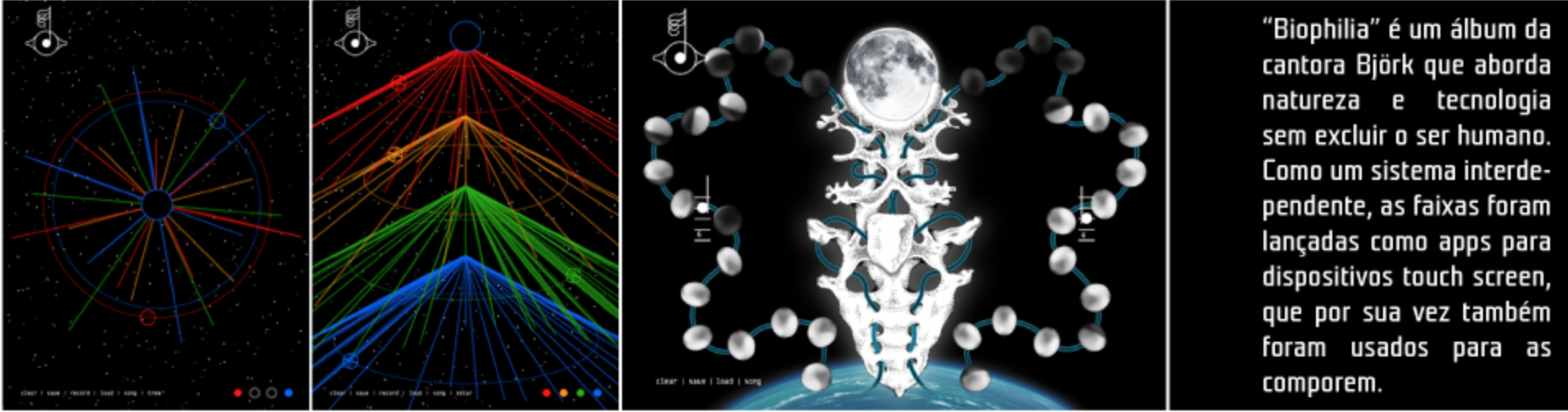

18-year-old software engineer Max Weisel was one of the guests that collaborated in the album Biophilia (2011 | Björk). Since then, he has been developing other projects related to music, such as the iboard, an instrument made with ipads that was used in Björk’s tour in 2012 Max also develops his personal projects such as Harpulum, Video Destroyer and Touchscreen Instrument, a work that is still in progress. |

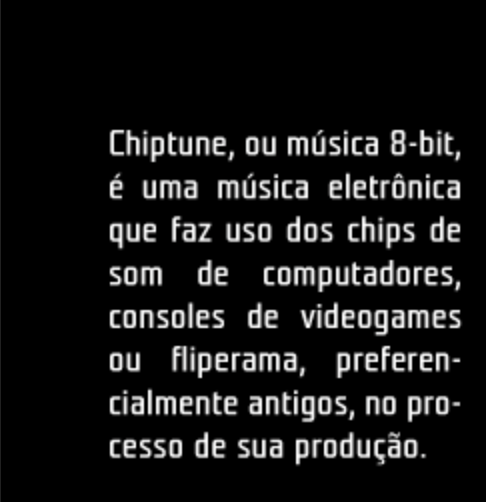

Video Games where the function of music is intrinsic to the game are related to other systems of sound, image and movement generation which date back to a time around the dawn of talking pictures. In 1930, Russian researcher Evegny Sholpo registers some forms in the soundtrack of a 35mm film with an optical instrument called Variophone. As it is projected, the film creates sounds that are similar to the ones in 8-bit music in the earliest Video Games. In the United Kingdom, Daphne Oram starts drawing sound pieces in films, leading to the development of Oramics, a musical composition machine that reminds us of an elaborated moviola.

Since the first video games, music is not treated as mere soundtrack. In many of them – such as “Moondust”, “Rez”, “BIT.TRIP”, “Dyad” – audio is the fundamental element, one that can’t be dissociated from the game itself.

In the 1960’s, cinema showed a longing for interactivity with the launching of Smell-O-Vision, a system that released smells according to the films, but the Czech feature film Kinoautomat was the first that had the audience interact with the story by using a control. This kind of interactive film has influenced other productions in cinema and TV, but one weakness is always the disrupted way in which the game is used in the narrative. Due to this disconnection, it’s worth noting that such projects consist of long cut scenes in a very limited game.

The sequence above is from the game series Metal Gear Solid (Kojima Productions), which became famous by breaking the fourth wall in an innovative way. In one at the scenes, a villain threatens not the avatar, but the player her/himself. The game accesses save data from other games in the console’s memory card and, as if kidnapping this information, threatens to delete it. Another villain asks the player to place the control on the floor. By using the joystick vibration resource, he also makes the control crawl, in a show of power that goes beyond screen limits.

Video Games provide interactive film projects with the ideal medium in which to develop. Famous films and series. such as Matrix and The Walking Dead, are delivered to consoles with new contents that further unfold the narrative. Film-based games are no longer barren reproductions on a different platform, with stages that could be anticipated from the action sequences in the original movies.

Heavy Rain is probably one of the clearest examples of the fictional narrative of cinema at work with video games. Its script features multiple possibilities and consequences. but unlike other interactive films or games with cut scenes, there is no rupture between game and film moments. Even though there is a main character, we also have to play with other characters to make the plot evolve. a fictional device that is often used in cinema. There are no limited lives or game over screens. any false move can mean the permanent loss of one of these avatars. The death of the avatar is incorporated to the plot, and there is no possibility of recovery.

With so many characters and diverse situations, players need to establish different kinds of interaction with game controls in order to solve challenges often intuitively. Joysticks no longer have specific functions for their buttons when pressed, but rather react according to each situation that is proposed .

ExistenZ (1999 | David Cronenberg) is one of the first video game-themed films that actually absorbs game characteristics in the cinema. Right at the beginning, video game designer Allegra Geller (Jennifer Jason-Leigh) announces, “The world of games is at a point of inflection. People are programmed to accept very little, yet the possibilities are so great.” Cronenberg brings to light the origin of technology in ourselves, videogames seem to be alive, and their connection with users takes place through an umbilical cord.

“Technology is us. There is no separation. It’s a pure expression of human creative will. […] And if it is at times dangerous and threatening, it is because we have within ourselves we have things within us that are dangerous, self-destructive and threatening, and this has expressed itself in various ways throughout technology. […] First of all, in the obvious ways – the eyes with binoculars, the ears with the telephone technology had to be an advancement of powers we knew we had. Then it gets more elaborate and more distant from us. More abstract. But it still all emanates from us. It’s us.”

– David Cronenberg

There are many who still regard videogames restrictively as children’s pastimes. The game Super Columbine Massacre RPG! (2005 | Danny Ledonne), about the school massacre in Oregon, USA, is worth remembering. Despite the media exploitation of the massacre – by exposing images that were captured by security cameras, as well as in several books and films the game gave rise to protests. This raises the creator’s question: “We can read about Columbine, we can watch Columbine, but we can’t play Columbine?” Regardless of the discomfort with violent content in games, even the ones that are based in real-life events, we must give up any assumption that interactivity with fiction implies a loss of awareness.

“Instead of deluding ourselves,

by thinking that fictions are real,

we become fiction.”

– Kendall Walton

Like cinema. video games can be organized in genres. Apart from genres that are exclusive for games – simulation, strategy, RPG – some overlap with film genres – such as action, thriller, and even documentary, The Cat and the Coup (2010 | Peter Brinson e Kurosh ValaNejad), a documentary game with a political theme, about Iranian prime-minister Mohammed Mossadegh, an icon in the anti-imperialistic fight. Every Day The Same Dream is a 20 game that looks more like a nihilistic animation short film.

Not only is technology a human extension, but art also projects our ideas and sensations. Along the 20th century, art has shown a craving for systems that are similar to what video games came to be, even before they were technologically feasible. If video games cannot be considered art, at least they emerge from an artistic desire.

Many of the questions that are still posed to videogames are equivalent to the ones that have emerged with cinema a long time ago. It seems that the possibilities of video games are as hard to calculate today. as unreachable, as it must have been for the audience of filmed theater in the beginning of the 20th century to imagine what was still to come with shot cutting and editing.

curators

Paulo Mendel

Gabriel Perin

São Paulo, Brasil | 2013